On the childhood trauma of Attila and Ágota Kristóf

The arrest of their father put an end to the five happiest years of their childhood: they had to leave their beloved town Kőszeg (Hungary) because of shame. Brother and sister, who later both became writers, experienced all this as being expelled from Paradise. We find plenty of vague or symbolic references to their family tragedy in their oeuvre, especially in Ágota’s depressing, often cruel novels, by which she gained world fame. Although the reason for the arrest has long been researchable in contemporary newspaper articles, literature on the Kristóf siblings is silent on the fact that their father was accused of raping little girls.

Both Ágota and Attila openly emphasized their admiration for Kőszeg. "We didn't even suspect at the time that this place would captivate us, and everything that we call happiness and beauty would be connected to it," Attila wrote in his memoirs. “I have always loved Kőszeg. This is the only town I feel close to”, said Ágota. They both chose the cemetery here as their final resting place, far from the ashes of their ancestors, their descendants, and the scenes of their successes. Oddly enough, there is no memorial plaque hanging on their former house in Árpád Square. The building holds haunting memories; a social taboo that has been encysted for decades and which can now be broken by an unexpectedly emerging archival document and the testimonies of two elderly witnesses.

The young Kálmán Kristóf.

Attila and Ágota's father Kálmán Kristóf (1905-1977), the eminent student of the teacher training college of Sopron, first got a job in the elementary school of a small Hungarian village called Csikvánd in 1926. It must have been in the nearby town of Pápa that he met his future wife, Antónia Turchányi from the Hungarian Highlands, with whom he had three children: Jenő (1934), Ágota (1935) and Attila (1938). The couple actively participated in the cultural and economic life of Csikvánd. In the summer, Kálmán regularly returned to his native village, Püspökmolnári, and held courses for local children. The unsuspecting parents thanked his voluntary commitment with backyard products; often so abundantly that he could barely get on the train with them.

The young Kálmán Kristóf.

Attila and Ágota's father Kálmán Kristóf (1905-1977), the eminent student of the teacher training college of Sopron, first got a job in the elementary school of a small Hungarian village called Csikvánd in 1926. It must have been in the nearby town of Pápa that he met his future wife, Antónia Turchányi from the Hungarian Highlands, with whom he had three children: Jenő (1934), Ágota (1935) and Attila (1938). The couple actively participated in the cultural and economic life of Csikvánd. In the summer, Kálmán regularly returned to his native village, Püspökmolnári, and held courses for local children. The unsuspecting parents thanked his voluntary commitment with backyard products; often so abundantly that he could barely get on the train with them.

According to the family legend, word of his dedication spread, and after eighteen years of school management experience (he had been the only teacher at the village school) he received a job offer from the teacher training institute in Kőszeg, beautiful little town on the Austrian-Hungarian border. The memories of the elderly of Csikvánd are different: a rumour about Kálmán started to circulate in the village. That could be the real reason for their searching for a new home. Distrust intensified especially after the mysterious suicide of a fourteen-year-old girl, Irén Zámolyi, in 1939.

The family moved to Kőszeg in the spring of 1944, when the school year ended on April 1 due to the Second World War. The beauty of Kőszeg amazed the three children, especially enchanting the hearts of Ágota and Attila. Some of her short stories and his recollections reflect their later unquenchable longing.

Ágota marked the first as her most memorable year in Kőszeg: the last, most difficult period of the war. “We were often scared, but we had a great time, because we didn't have to go to school” she declared in an interview. Like guttersnipes, she and his brother Jenő, just over a year older, stole potatoes, corn, and cigarettes, wandered the streets, “screwed around”, while their little brother, six-year-old Attila, was hanging on to their mother at home. Ágota was nine and Jeno was ten; the adventures of the two at the time inspired Ágota’s first and most famous novel, The Notebook, in which she portrays themselves as nine-year-old twin boys who harden their hearts. She partly modeled the malicious Grandmother on their own mother.

Meanwhile their father Kálmán was serving in the army on the front. He could hardly immerse himself in his work as a teacher trainer (he became head of the first class at the practising school, thus becoming Attila's teacher) he received the military draft and was ordered to Germany as sergeant and scribe. There he survived the train explosion at Celle, then escaped in a cunning way: in an open order he gave a command to himself to return home. It is stunning how his figure appears in the final scene of Ágota's novel: returning from the front he asks his twins to help him cross the border strip. Just as the boys have calculated, he steps on a grenade and explodes, and one of the kids can escape abroad over his dead body. “She sentenced our father to death in The Notebook” – Attila summerized Ágota's message.

Kálmán Kristóf (back centre) with his class in Kőszeg around 1947. Attila Kristóf is probably the boy on the far right in the first row.

Kálmán Kristóf (back centre) with his class in Kőszeg around 1947. Attila Kristóf is probably the boy on the far right in the first row.

Knowing the biographical background it is no wonder that, despite the wartime conditions, Ágota most fondly remembered the few months she spent without her father, nor that the symbolic patricide appears again and again in her following three novels.

After three school years in Kőszeg, in October 1948, Kálmán was put on trial for sexually abusing his female students and sentenced to seven years in prison. The entire court file was destroyed at the end of the 1970s, but a copy of the order was recently unearthed from the archives, and it reveals that Kálmán Kristóf abused a total of 17 children during his 22 years as a teacher in Csikvánd and Kőszeg, eight of whom he raped. They were all his pupils, little girls under the age of twelve. From contemporary newspaper articles and the notes of László Székely, the abbot of Kőszeg, it is revealed that his youngest victim was only seven years old, and according to the rumour he used hypnosis, and with the middle-school girls also chloroform to break the resistance (as in the last two months he worked as a Maths-Physics-Chemistry teacher and so the school lab was available for him).

In addition to the children's statements, the accusation of abuse was supported by medical opinions as well as Kálmán's heartfelt confession.

His wife, who knew nothing, collapsed at the police station when confronted with what had happened. According to Attila Kristóf's widow, Ágnes Ujlaki, who helped to reconstruct the story, Antónia allegedly cried and sobbed during the interrogation and shouted: “That's not true! It's a slander!” To this day the descendants have known a legend of a conceptual trial, and believed that Kálmán Kristóf's molestations were much milder. In an interview, Ágota suggests that Antónia's hair turned gray from shock.

Kálmán was probably sent to the prison of Sárvár. The family went from a peaceful bourgeois life to an existential and economic collapse almost overnight.

The Kristóf family in 1948, a few months before Kálmán's arrestment.

The Kristóf family in 1948, a few months before Kálmán's arrestment.

After more than seventy years, two of Kálmán's former students, an elderly lady and a man, testified about the details. Both were Attila's classmates, and the lady used to be his playmate, too. Despite the fact that Kálmán was undoubtedly an enthusiastic, knowledgeable and experimental teacher ( in 1947 he published two issues of his self-edited pedagogical magazine entitled “New Education”), they remember him as being very strict, which is in line with the Kristóf siblings' opinion. The little girl was invited several times to the Kristófs where she played with Attila in the yard, then Kálmán moved into a room with her under the guise of tutoring. This is where the molestations began and they continued at the school, where after the lessons the man opened the classroom door narrowly so that the children could only leave one by one, and gave an order to her: “You stay here!” The lady's firm claim is that the teacher avoided any stunning: he took advantage of her mere respect for authority. “It didn't even cross my mind to object. What the teacher said had to be like that”, she remembered. In the same way, the tradition of respect for authority, as well as the lack of fundamental knowledge about sexuality and intimacy, which was treated then as taboo, prevented her from complaining to her parents. The scandal broke out only months later, thanks to two molested teenagers of the local orphanage, who reported to a female teacher about the man's confidential approach and violence.

The lady owes it to the justice system and to her good relationship with her father that, despite the abuse and the ordeal of interrogations, she was able to become a friendly, open adult, free of harmful passions. However, she was not helped to fully come to terms with the trauma, and according to her statement, she has always abstained from physical contact, and as a young woman she suffered from functional infertility for a decade.

After the trial held in the castle of Kőszeg, Antónia Turchányi fled from shame. She did not accept the teaching job offered in one of the local schools (she should have got divorced to get it); rather, she looked for work in remote settlements. A year later she became governess in the correctional institution for girls in Ikervár, about 25 miles from Kőszeg, but from there she could return home only at weekends. First she enrolled thirteen-year-old Ágota and ten-year-old Attila in a student dormitory in Kőszeg; fourteen-year-old Jenő was accepted by the dormitory of the Benedictine boys' grammar school which he attended anyway. However, Attila ran away after the first night, so Antónia had to come up with a new solution. In the end, for about half a year, the three kids remained at home without any adults on weekdays – Jenő had to take care of his little sister and brother, and the neighbour Mrs. Szász supervised them nominally. The front door remained locked, the kids passed through a window opening from the high verandah where they climbed up on the vines. In the evenings, they walked on the rooftops, read their father's library of hundreds of volumes which had been forbidden for them until then, and also Mrs. Szász's crime novels; and they loved each other very much.

According to Attila's recollections, this wild freedom (which he called “the golden age” of their childhood) ended when Antónia came home one weekend to find lice. Although the kids took it as a game, since Ágota and Attila were competing to see which could comb more lice out of their hair, their mother despaired and made a new decision. At the end of October 1950, she took Attila to Ikervár with her, transferred Ágota from the girls' high school in Kőszeg to Szombathely, and Jenő stayed in the dormitory of the boys' grammar school in Kőszeg.

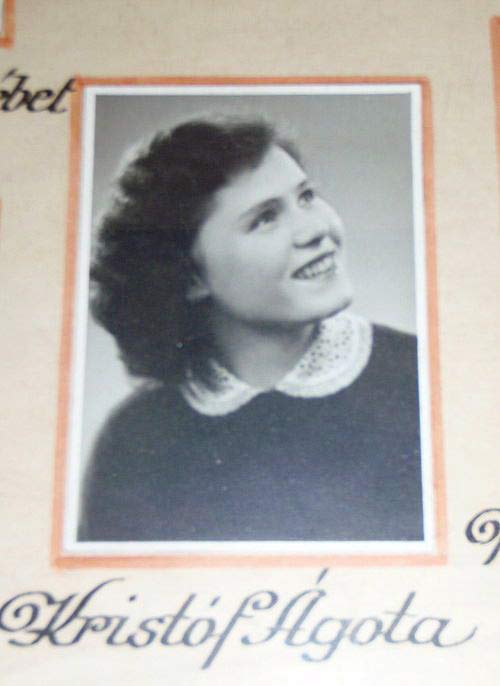

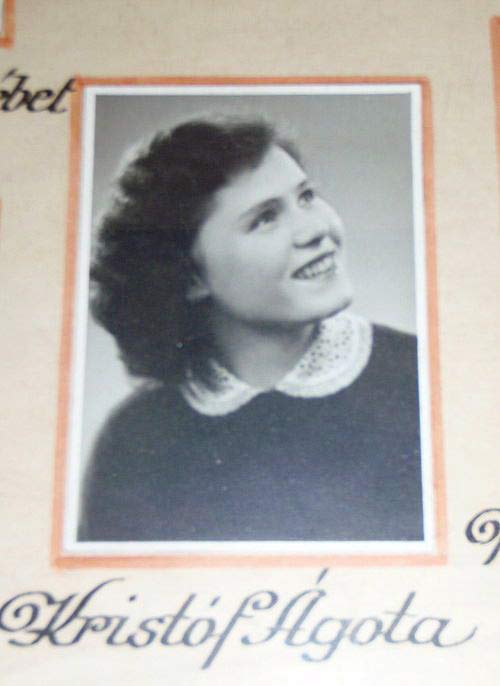

Ágota as a graduating high school student.

For the siblings, the separation from each other meant the final, greatest damage. “The golden thread of childhood was torn apart” – wrote Ágota, with an unusual emotionality. She had a hard time coping with the strict timetable of the boarding school in Szombathely. At night she cried under the covers; and in the monotonous solitude of the study room, she began writing a coded diary. (Her notes were later allegedly burned.) On the surface, however, she was a pride of the school, the clown and center of the company.

Ágota as a graduating high school student.

For the siblings, the separation from each other meant the final, greatest damage. “The golden thread of childhood was torn apart” – wrote Ágota, with an unusual emotionality. She had a hard time coping with the strict timetable of the boarding school in Szombathely. At night she cried under the covers; and in the monotonous solitude of the study room, she began writing a coded diary. (Her notes were later allegedly burned.) On the surface, however, she was a pride of the school, the clown and center of the company.

Meanwhile, Antónia sank deeper and deeper financially. When Ágota visited her at her current workplace, in a small basement room, she was earning her living by packing rat poison. From the age of fourteen, all three children worked every summer.

After graduation, Jenő, who had perfect pitch and a beautiful voice, was admitted to the Budapest Conservatory. In the meantime, he was working on the construction of the third subway line. The load proved too heavy; after two years he interrupted his studies as an opera singer, enlisted in the army, then in 1956 he got married and from then lived in various settlements of Western Hungary. He started a family and became a manager of a construction company in Zalaegerszeg.

Attila attended the last semester of elementary school in Pápa. He stayed at his maternal grandparents', at the beginning he specifically slept between his grandfather and grandmother. His mother had been probably forced to make another change due to the closure of the correctional institute in Ikervár. First she became an assistant of a shepherd on a farm near Csákvár, then a payrole accountant. Attila continued his studies at a grammar school in Pápa. Just like his sister, he was an excellent student and won academic competitions one after another.

Kálmán was released in 1953 at the two-thirds point of his sentence. “Hugged by a confused stranger who avoided our gaze, we were breathing hard,” Attila wrote. During his years in prison, Kálmán learned to be a mason and an accountant. It was thanks to the latter that he was hired by a construction company in Zalaegerszeg as a post-calculator. A few years later the local newspaper reported on his creativity, professional progress and appreciation. He introduced several useful reforms at the company; he became an “innovation lecturer” who, according to his own admission, always strived for something “more perfect”. The paper also gave Kálmán opportunities for literary experiments: in the early sixties, four of his short stories were published in the cultural supplement.

His wife followed him to Zalaegerszeg where she got a job in horticulture. In the beginning they lived in a laundry room, then they built a simple house with their own hands, without a bathroom, in the suburbs. Despite appearances Antónia never forgave her husband. Their cohabitation was plagued by bitter quarrels during which the woman scolded her husband and Kálmán humbly tolerated it. The reason for his morbid desires could have been his fear of adult women, which may have been instilled in him as a small child, under the hands of his embittered, cruel mother. Attila writes in his autobiographical novel: “My father suffered from this until his death. He paid for his mother's harshness, and he was also gentle and weak in his own way.”

Ágota graduated a year after her father's release. She planned her future with her parents in Zalaegerszeg, just like Jenő, but then, in an unexpected twist, she married her headmaster and history teacher, János Béri. While Antónia welcomed the decision (according to Ágota, she was happy to finally know her safe), Attila, who always admired his sister, was shocked. “I didn't know she was running away,” he wrote later. He could explain the turn by saying Ágota sought independence from an early age, although this “ultimately resulted in the creation of more relationships and dependencies than usual.”

The young couple had barely lived two years in Kőszeg, just opposite the former house of the Kristóf family, when the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 broke out and they decided to defect because of János Béri's political views. They fled across the border to Austria with their daughter who was only a few months old. Ágota wanted to go to the United States, to his paternal uncles, but after six months the authorities directed them back to Europe and provided them with a place in Neuchatel, Switzerland. Béri received a scholarship at the University of Basel, majoring in biology, while Ágota had to completely give up on her previous dreams of further education. She worked in a watch factory as a semi-skilled worker for five years, and she didn't even have the opportunity to learn French at a basic level. She supported the small family with her earnings, while she felt illiterate – she, who was self-taught and learned to read at the age of four. She had communication difficulties with her own child, too, who absorbed some language skills at the nursery school.

She finally divorced Béri after seven years and enrolled in a French language course, but her second husband, the photojournalist Jean-Pierre Baillod, also hindered her intellectual advancement. He frowned at the fact that Ágota was achieving more and more success in the local theatre life as an author. “Her personal life...” - wrote Attila - “was never in order. She divorced her second husband, from whom her two younger children were born, in fear. She expressed this in her own peculiar way by saying that familicide is not uncommon in Switzerland.”

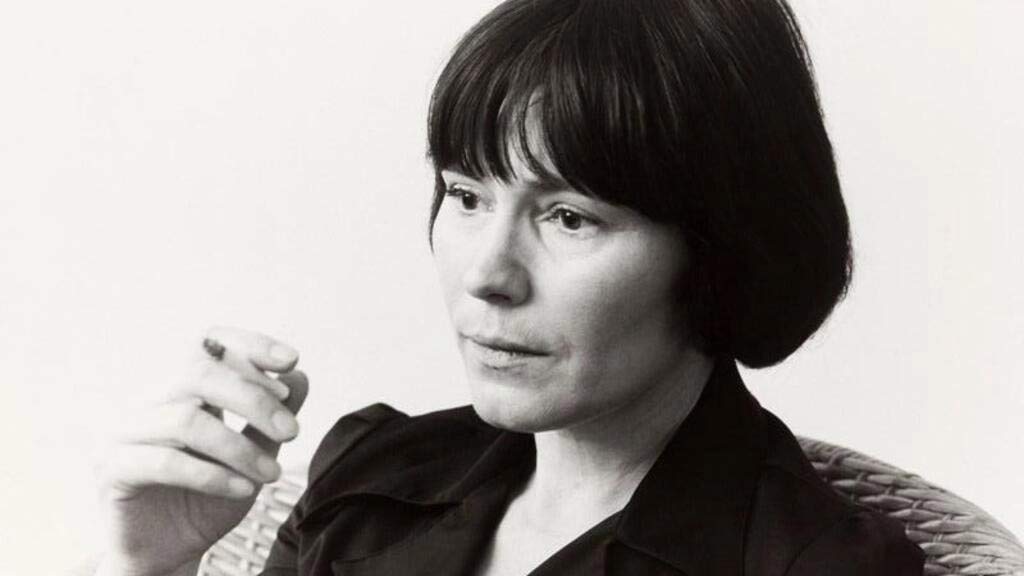

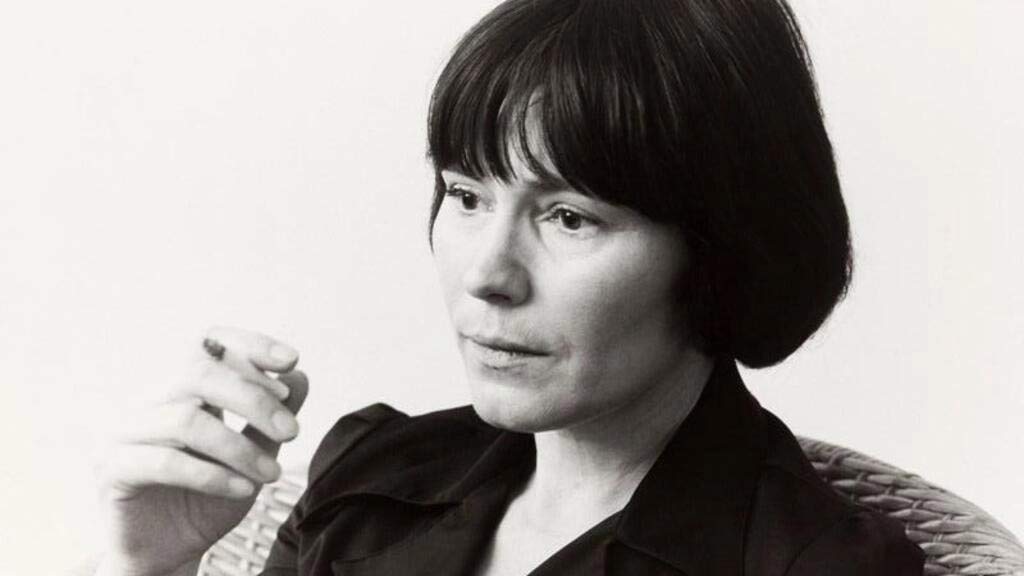

The writer Agota Kristof.

For her, writing was an escape from personal failures. Even as a high school student she acquired moody poems and funny scenes portraying teachers (the latter were performed with her friends, too), but in Switzerland she was forced to resort to a stripped-down style due to her insecurity in the French language. At first she wrote short stage works and audio plays, then she remembered the self-disciplining and cruel exercises she had once played with Jenő, which evoke the methods of “black pedagogy”, still fashionable at the beginning of the twentieth century; and the first novel began to take shape.

The writer Agota Kristof.

For her, writing was an escape from personal failures. Even as a high school student she acquired moody poems and funny scenes portraying teachers (the latter were performed with her friends, too), but in Switzerland she was forced to resort to a stripped-down style due to her insecurity in the French language. At first she wrote short stage works and audio plays, then she remembered the self-disciplining and cruel exercises she had once played with Jenő, which evoke the methods of “black pedagogy”, still fashionable at the beginning of the twentieth century; and the first novel began to take shape.

Her younger brother, Attila, had been a journalist for a national daily newspaper and a popular crime writer for decades when The Notebook was produced on fifty-year-old Ágota's Swiss desk. It was a shocking story full of sexual perversions, which, according to the general interpretations, is about the atrocities of the Second World War and the survival strategies of two twins. Although only the third publisher approached was willing to deal with the manuscript, it achieved frenetic success after its publication in 1986. It was translated into more than thirty-four languages, won countless international awards, created a cult in the Far East, and after the writer's death, was revived in János Szász's film adaptation which won several professional accolades. After The Notebook, Ágota continued to write tirelessly and with great diligence, and at the peak of her career she was at the forefront of modern European literature; critics refer to her as one of the most important authors of the 21st century in francophone literature. Her novels were listed bestsellers not only in French but also in German, Japanese and Korean. She received the highest Hungarian recognition for artists a few months before her death.

According to her own admission, she could not get rid of the figure of the twin boys (metaphorically, therefore, of her own childhood memories), and she continued to write about their fate in two novels. These (The Proof and The Third Lie), along with her first novel, form her Trilogy. Later she also published a short novel entitled Yesterday, which is again full of autobiographical references; as well as countless short stories and plays with a depressing atmosphere.

A scene from the movie The Notebook by János Szász.

In the court order summarizing Kálmán's crimes, only names of his students are listed, Ágota's is not. Still, she was undoubtedly more damaged mentally than her two brothers. In her nightmares and during her writing, which was probably self-therapy for her, she constantly puzzled over her childhood experiences and her relationship with her father. The ever-recurring motif of patricide testifies to the fact that her desire for revenge against Kálmán did not subside for decades. Even in 2009, more than thirty years after her father's death, she told one of her Hungarian translators, András Petőcz, that the last scene of The Notebook, in which one of the boys escapes over the dead body of his father, whom they have deliberately sent to death, was “beautiful” for her. When Petőcz instinctively asks if The Notebook is about how to get over one's father, the writer answers with her characteristic conciseness: “Yes, a little, maybe. Psychologists have to analyze this.”

A scene from the movie The Notebook by János Szász.

In the court order summarizing Kálmán's crimes, only names of his students are listed, Ágota's is not. Still, she was undoubtedly more damaged mentally than her two brothers. In her nightmares and during her writing, which was probably self-therapy for her, she constantly puzzled over her childhood experiences and her relationship with her father. The ever-recurring motif of patricide testifies to the fact that her desire for revenge against Kálmán did not subside for decades. Even in 2009, more than thirty years after her father's death, she told one of her Hungarian translators, András Petőcz, that the last scene of The Notebook, in which one of the boys escapes over the dead body of his father, whom they have deliberately sent to death, was “beautiful” for her. When Petőcz instinctively asks if The Notebook is about how to get over one's father, the writer answers with her characteristic conciseness: “Yes, a little, maybe. Psychologists have to analyze this.”

Indeed, deciphering Ágota Kristóf's life work and her spiritual world can be an exciting task for psychologists. It would be worth analyzing whether the disillusioned worldview, recurring nightmares, self-harm and dissociation (“someone else hurts”) that can be read in her novels indicate chronic abuse. Why did she almost always place herself in a male narrative? If she very rarely told stories from a female role, why did that woman always have to be oppressed or abused by a man, or annoyed to the extreme by her husband? Why did she feel the need to present paraphilic (pedophilic, zoophilic, urophilic, lust killer) scenes that offend public taste? Why do her victims of sexual abuse (in The Notebook in all cases children!) cooperate with their perpetrators? Why do the fictitious twins decide when writing their diaries, as Ágota does with all her works, to suppress the emotions associated with the events instead of writing them down? Why doesn't she depict sexual abuse as a crime, and why do her victims remain in a good relationship with the perpetrator?

Ágota was attacked several times in the French-speaking world due to the depiction of sexual deviance, especially as the Trilogy is compulsory reading in high schools in Switzerland, but it is also part of the curriculum in several high and elementary schools in France. The writer defended herself by saying that sexual violence was part of the reality of war in Hungary. The argument, however, is flawed, since only the first of the three novels takes place during the time of the global conflagration, while the other two also abound in perversions. On the other hand, they are not simply about violence, but often paraphilias. Moreover, in almost all cases, the perpetrator and the victim live side by side even in peacetime. Despite many controversies, her Trilogy has retained its place among French-language classics and compulsory readings.

Clarity about her works was made significantly difficult by the fact that Ágota consistently portrayed her father in interviews as if he had been sentenced to five years in prison as a military deserter or for political reasons. After all, what else could she have said? Journalist Lívia Ölbei understood that in her life work she “tells everything in the world – what is possible to tell”. Only in “cryptic writing”, as in her diary. Only those who have the key to the solution, her biography without taboos, understand it.

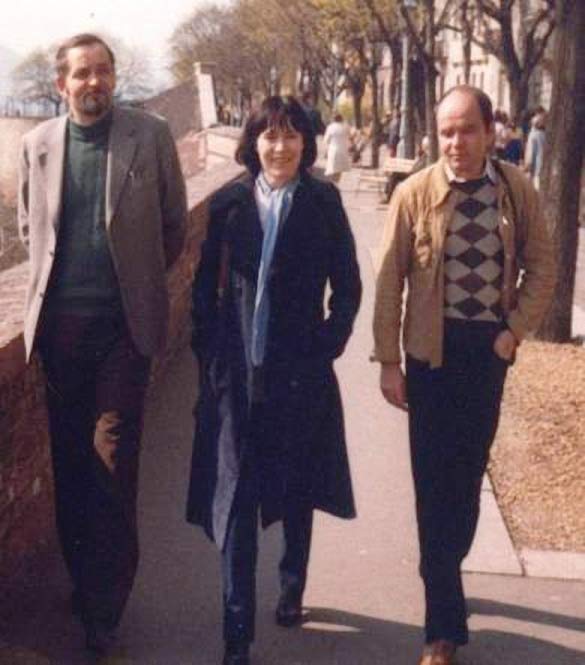

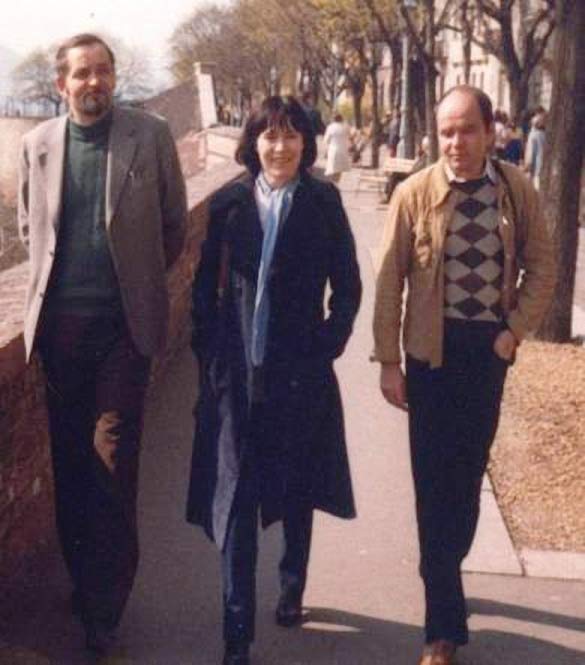

Jenő, Ágota and Attila Kristóf in Kőszeg.

Recovery from the family tragedy was significantly easier for Ágota's brothers. In a late interview, Jenő indicated that he did not experience their childhood as dark as his sister and that he remembers the wild freedom more than the difficulties. (Although he adds that the adults did not help them process “the experienced things”.) He remained a good-humoured and friendly person even in his old age.

Jenő, Ágota and Attila Kristóf in Kőszeg.

Recovery from the family tragedy was significantly easier for Ágota's brothers. In a late interview, Jenő indicated that he did not experience their childhood as dark as his sister and that he remembers the wild freedom more than the difficulties. (Although he adds that the adults did not help them process “the experienced things”.) He remained a good-humoured and friendly person even in his old age.

For the younger brother, Attila, writing was probably self-therapy in the same way as for Ágota; the creative imprint of a constant, seemingly irrational childhood fear. He is now considered a classic of twentieth-century Hungarian crime writing and a doyen of feuilletonists; his countless detective stories, works of horror fiction, and his two volumes of reports on the work of the Budapest Police Headquarters' murder squad, all helped him to get rid of his demons. Although like his sister, he himself suffered from depression in the middle of his life, their basic worldviews were diametrically opposed. Attila was always driven by the desire for a happy ending, not only in his fictions but also in relation to the knot that arose in his family's life. According to his autobiographic novel, he believed until the end that his parents' names were “written down in heaven”. “Until the last minute I hoped that we would fall on our knees in front of each other, crying for mercy, I thought our souls could be saved”, he wrote. Antónia Turchányi could have been a key player in a healing family conversation, but her strictness and stubbornness were unyielding even after Kálmán's death in 1977.

Attila, unlike Ágota and Jenő, loved his father, although this feeling was mixed with fear towards both parents. Still, he may have been characterized by the ability to “love beyond fate”, the absence of which was pointed out by essayist Zsolt Mórocz in Ágota's works.

In the mid-1980s, already a family man, Attila returned to Kőszeg from Budapest and restlessly searched for the truth of his past, even at the risk of ruin. Just like Sophocles' King Oedipus. However, he found nothing. In almost forty years, the small town apparently forgot the case of the perverted teacher, and the court material was destroyed. Attila could therefore only tell the story, antecedents and consequences of their “expulsion from Paradise” based on his own and his family members' memories. With his twelfth book, “Oedipus circling” published in Hungarian in 1987 – this bitter, honest memoir disguised as fiction – he did as much as possible to save the souls of his family members. (Although he did not name the crime, only vaguely alluded to it.) He gives such a precise and sometimes confidential description of Ágota (under the pseudonym “Zsuzsa”), that it almost seems irresponsible. He could not have guessed that his sister, who had language difficulties, would become a world-famous writer within a few years, whom anyone could easily identify with “Zsuzsa” based on the biographies published about her; and with the help of the works and statements of the two siblings, the family cataclysm can be reconstructed without any particular obstacles. Perhaps there are no coincidences: Ágota wrote her first novel without consultation, in parallel with Attila's Oedipus, and both elaborate on their memories of Kőszeg.

Attila consistently denied the realistic foundations of “Oedipus”, and only after Ágota's death, in the obituary written about her, did he openly acknowledge its autobiographical nature. However, not only the main characters, children and their parents, but also the more important secondary characters are verifiably real figures: for example “Florence” who was murdered in the neighbourhood of the Kristóf family, and Orrnix with her damaged face. Their figures or stories, slightly distorted, were also drawn by Ágota in The Notebook.

Although biographical descriptions of the Kristóf family, memories, interviews conducted in Hungarian, art analyzes, and even the biography and “memorial book” about Ágota published in her graduation town Szombathely in 2016, are all silent about the sexuality prominently displayed in her works and the perverse tendencies of Kálmán Kristóf, the case has always remained a topic of conversation “behind the scenes”. It is not impossible that this was the real reason for the writer's neglect of her homeland.

Since the people directly affected have all passed away: Ágota in 2011, Attila in 2015 and Jenő in 2017, now there should be no obstacle to unfolding the tragedy of the Kristóf siblings factually, processing it on a social level, and commemorating Kálmán Kristóf's at least seventeen victims instead of one-sidedly praising his spiritual legacy.

But by uncovering the terrifying depths and tirelessly fought heights of their true story will Ágota and Attila's wandering souls be calmed? I do not know...

The young Kálmán Kristóf.

The young Kálmán Kristóf.According to the family legend, word of his dedication spread, and after eighteen years of school management experience (he had been the only teacher at the village school) he received a job offer from the teacher training institute in Kőszeg, beautiful little town on the Austrian-Hungarian border. The memories of the elderly of Csikvánd are different: a rumour about Kálmán started to circulate in the village. That could be the real reason for their searching for a new home. Distrust intensified especially after the mysterious suicide of a fourteen-year-old girl, Irén Zámolyi, in 1939.

The family moved to Kőszeg in the spring of 1944, when the school year ended on April 1 due to the Second World War. The beauty of Kőszeg amazed the three children, especially enchanting the hearts of Ágota and Attila. Some of her short stories and his recollections reflect their later unquenchable longing.

Ágota marked the first as her most memorable year in Kőszeg: the last, most difficult period of the war. “We were often scared, but we had a great time, because we didn't have to go to school” she declared in an interview. Like guttersnipes, she and his brother Jenő, just over a year older, stole potatoes, corn, and cigarettes, wandered the streets, “screwed around”, while their little brother, six-year-old Attila, was hanging on to their mother at home. Ágota was nine and Jeno was ten; the adventures of the two at the time inspired Ágota’s first and most famous novel, The Notebook, in which she portrays themselves as nine-year-old twin boys who harden their hearts. She partly modeled the malicious Grandmother on their own mother.

Meanwhile their father Kálmán was serving in the army on the front. He could hardly immerse himself in his work as a teacher trainer (he became head of the first class at the practising school, thus becoming Attila's teacher) he received the military draft and was ordered to Germany as sergeant and scribe. There he survived the train explosion at Celle, then escaped in a cunning way: in an open order he gave a command to himself to return home. It is stunning how his figure appears in the final scene of Ágota's novel: returning from the front he asks his twins to help him cross the border strip. Just as the boys have calculated, he steps on a grenade and explodes, and one of the kids can escape abroad over his dead body. “She sentenced our father to death in The Notebook” – Attila summerized Ágota's message.

Kálmán Kristóf (back centre) with his class in Kőszeg around 1947. Attila Kristóf is probably the boy on the far right in the first row.

Kálmán Kristóf (back centre) with his class in Kőszeg around 1947. Attila Kristóf is probably the boy on the far right in the first row.Knowing the biographical background it is no wonder that, despite the wartime conditions, Ágota most fondly remembered the few months she spent without her father, nor that the symbolic patricide appears again and again in her following three novels.

After three school years in Kőszeg, in October 1948, Kálmán was put on trial for sexually abusing his female students and sentenced to seven years in prison. The entire court file was destroyed at the end of the 1970s, but a copy of the order was recently unearthed from the archives, and it reveals that Kálmán Kristóf abused a total of 17 children during his 22 years as a teacher in Csikvánd and Kőszeg, eight of whom he raped. They were all his pupils, little girls under the age of twelve. From contemporary newspaper articles and the notes of László Székely, the abbot of Kőszeg, it is revealed that his youngest victim was only seven years old, and according to the rumour he used hypnosis, and with the middle-school girls also chloroform to break the resistance (as in the last two months he worked as a Maths-Physics-Chemistry teacher and so the school lab was available for him).

In addition to the children's statements, the accusation of abuse was supported by medical opinions as well as Kálmán's heartfelt confession.

His wife, who knew nothing, collapsed at the police station when confronted with what had happened. According to Attila Kristóf's widow, Ágnes Ujlaki, who helped to reconstruct the story, Antónia allegedly cried and sobbed during the interrogation and shouted: “That's not true! It's a slander!” To this day the descendants have known a legend of a conceptual trial, and believed that Kálmán Kristóf's molestations were much milder. In an interview, Ágota suggests that Antónia's hair turned gray from shock.

Kálmán was probably sent to the prison of Sárvár. The family went from a peaceful bourgeois life to an existential and economic collapse almost overnight.

The Kristóf family in 1948, a few months before Kálmán's arrestment.

The Kristóf family in 1948, a few months before Kálmán's arrestment.After more than seventy years, two of Kálmán's former students, an elderly lady and a man, testified about the details. Both were Attila's classmates, and the lady used to be his playmate, too. Despite the fact that Kálmán was undoubtedly an enthusiastic, knowledgeable and experimental teacher ( in 1947 he published two issues of his self-edited pedagogical magazine entitled “New Education”), they remember him as being very strict, which is in line with the Kristóf siblings' opinion. The little girl was invited several times to the Kristófs where she played with Attila in the yard, then Kálmán moved into a room with her under the guise of tutoring. This is where the molestations began and they continued at the school, where after the lessons the man opened the classroom door narrowly so that the children could only leave one by one, and gave an order to her: “You stay here!” The lady's firm claim is that the teacher avoided any stunning: he took advantage of her mere respect for authority. “It didn't even cross my mind to object. What the teacher said had to be like that”, she remembered. In the same way, the tradition of respect for authority, as well as the lack of fundamental knowledge about sexuality and intimacy, which was treated then as taboo, prevented her from complaining to her parents. The scandal broke out only months later, thanks to two molested teenagers of the local orphanage, who reported to a female teacher about the man's confidential approach and violence.

The lady owes it to the justice system and to her good relationship with her father that, despite the abuse and the ordeal of interrogations, she was able to become a friendly, open adult, free of harmful passions. However, she was not helped to fully come to terms with the trauma, and according to her statement, she has always abstained from physical contact, and as a young woman she suffered from functional infertility for a decade.

After the trial held in the castle of Kőszeg, Antónia Turchányi fled from shame. She did not accept the teaching job offered in one of the local schools (she should have got divorced to get it); rather, she looked for work in remote settlements. A year later she became governess in the correctional institution for girls in Ikervár, about 25 miles from Kőszeg, but from there she could return home only at weekends. First she enrolled thirteen-year-old Ágota and ten-year-old Attila in a student dormitory in Kőszeg; fourteen-year-old Jenő was accepted by the dormitory of the Benedictine boys' grammar school which he attended anyway. However, Attila ran away after the first night, so Antónia had to come up with a new solution. In the end, for about half a year, the three kids remained at home without any adults on weekdays – Jenő had to take care of his little sister and brother, and the neighbour Mrs. Szász supervised them nominally. The front door remained locked, the kids passed through a window opening from the high verandah where they climbed up on the vines. In the evenings, they walked on the rooftops, read their father's library of hundreds of volumes which had been forbidden for them until then, and also Mrs. Szász's crime novels; and they loved each other very much.

According to Attila's recollections, this wild freedom (which he called “the golden age” of their childhood) ended when Antónia came home one weekend to find lice. Although the kids took it as a game, since Ágota and Attila were competing to see which could comb more lice out of their hair, their mother despaired and made a new decision. At the end of October 1950, she took Attila to Ikervár with her, transferred Ágota from the girls' high school in Kőszeg to Szombathely, and Jenő stayed in the dormitory of the boys' grammar school in Kőszeg.

Ágota as a graduating high school student.

Ágota as a graduating high school student.Meanwhile, Antónia sank deeper and deeper financially. When Ágota visited her at her current workplace, in a small basement room, she was earning her living by packing rat poison. From the age of fourteen, all three children worked every summer.

After graduation, Jenő, who had perfect pitch and a beautiful voice, was admitted to the Budapest Conservatory. In the meantime, he was working on the construction of the third subway line. The load proved too heavy; after two years he interrupted his studies as an opera singer, enlisted in the army, then in 1956 he got married and from then lived in various settlements of Western Hungary. He started a family and became a manager of a construction company in Zalaegerszeg.

Attila attended the last semester of elementary school in Pápa. He stayed at his maternal grandparents', at the beginning he specifically slept between his grandfather and grandmother. His mother had been probably forced to make another change due to the closure of the correctional institute in Ikervár. First she became an assistant of a shepherd on a farm near Csákvár, then a payrole accountant. Attila continued his studies at a grammar school in Pápa. Just like his sister, he was an excellent student and won academic competitions one after another.

Kálmán was released in 1953 at the two-thirds point of his sentence. “Hugged by a confused stranger who avoided our gaze, we were breathing hard,” Attila wrote. During his years in prison, Kálmán learned to be a mason and an accountant. It was thanks to the latter that he was hired by a construction company in Zalaegerszeg as a post-calculator. A few years later the local newspaper reported on his creativity, professional progress and appreciation. He introduced several useful reforms at the company; he became an “innovation lecturer” who, according to his own admission, always strived for something “more perfect”. The paper also gave Kálmán opportunities for literary experiments: in the early sixties, four of his short stories were published in the cultural supplement.

His wife followed him to Zalaegerszeg where she got a job in horticulture. In the beginning they lived in a laundry room, then they built a simple house with their own hands, without a bathroom, in the suburbs. Despite appearances Antónia never forgave her husband. Their cohabitation was plagued by bitter quarrels during which the woman scolded her husband and Kálmán humbly tolerated it. The reason for his morbid desires could have been his fear of adult women, which may have been instilled in him as a small child, under the hands of his embittered, cruel mother. Attila writes in his autobiographical novel: “My father suffered from this until his death. He paid for his mother's harshness, and he was also gentle and weak in his own way.”

Ágota graduated a year after her father's release. She planned her future with her parents in Zalaegerszeg, just like Jenő, but then, in an unexpected twist, she married her headmaster and history teacher, János Béri. While Antónia welcomed the decision (according to Ágota, she was happy to finally know her safe), Attila, who always admired his sister, was shocked. “I didn't know she was running away,” he wrote later. He could explain the turn by saying Ágota sought independence from an early age, although this “ultimately resulted in the creation of more relationships and dependencies than usual.”

The young couple had barely lived two years in Kőszeg, just opposite the former house of the Kristóf family, when the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 broke out and they decided to defect because of János Béri's political views. They fled across the border to Austria with their daughter who was only a few months old. Ágota wanted to go to the United States, to his paternal uncles, but after six months the authorities directed them back to Europe and provided them with a place in Neuchatel, Switzerland. Béri received a scholarship at the University of Basel, majoring in biology, while Ágota had to completely give up on her previous dreams of further education. She worked in a watch factory as a semi-skilled worker for five years, and she didn't even have the opportunity to learn French at a basic level. She supported the small family with her earnings, while she felt illiterate – she, who was self-taught and learned to read at the age of four. She had communication difficulties with her own child, too, who absorbed some language skills at the nursery school.

She finally divorced Béri after seven years and enrolled in a French language course, but her second husband, the photojournalist Jean-Pierre Baillod, also hindered her intellectual advancement. He frowned at the fact that Ágota was achieving more and more success in the local theatre life as an author. “Her personal life...” - wrote Attila - “was never in order. She divorced her second husband, from whom her two younger children were born, in fear. She expressed this in her own peculiar way by saying that familicide is not uncommon in Switzerland.”

The writer Agota Kristof.

The writer Agota Kristof.Her younger brother, Attila, had been a journalist for a national daily newspaper and a popular crime writer for decades when The Notebook was produced on fifty-year-old Ágota's Swiss desk. It was a shocking story full of sexual perversions, which, according to the general interpretations, is about the atrocities of the Second World War and the survival strategies of two twins. Although only the third publisher approached was willing to deal with the manuscript, it achieved frenetic success after its publication in 1986. It was translated into more than thirty-four languages, won countless international awards, created a cult in the Far East, and after the writer's death, was revived in János Szász's film adaptation which won several professional accolades. After The Notebook, Ágota continued to write tirelessly and with great diligence, and at the peak of her career she was at the forefront of modern European literature; critics refer to her as one of the most important authors of the 21st century in francophone literature. Her novels were listed bestsellers not only in French but also in German, Japanese and Korean. She received the highest Hungarian recognition for artists a few months before her death.

According to her own admission, she could not get rid of the figure of the twin boys (metaphorically, therefore, of her own childhood memories), and she continued to write about their fate in two novels. These (The Proof and The Third Lie), along with her first novel, form her Trilogy. Later she also published a short novel entitled Yesterday, which is again full of autobiographical references; as well as countless short stories and plays with a depressing atmosphere.

A scene from the movie The Notebook by János Szász.

A scene from the movie The Notebook by János Szász.Indeed, deciphering Ágota Kristóf's life work and her spiritual world can be an exciting task for psychologists. It would be worth analyzing whether the disillusioned worldview, recurring nightmares, self-harm and dissociation (“someone else hurts”) that can be read in her novels indicate chronic abuse. Why did she almost always place herself in a male narrative? If she very rarely told stories from a female role, why did that woman always have to be oppressed or abused by a man, or annoyed to the extreme by her husband? Why did she feel the need to present paraphilic (pedophilic, zoophilic, urophilic, lust killer) scenes that offend public taste? Why do her victims of sexual abuse (in The Notebook in all cases children!) cooperate with their perpetrators? Why do the fictitious twins decide when writing their diaries, as Ágota does with all her works, to suppress the emotions associated with the events instead of writing them down? Why doesn't she depict sexual abuse as a crime, and why do her victims remain in a good relationship with the perpetrator?

Ágota was attacked several times in the French-speaking world due to the depiction of sexual deviance, especially as the Trilogy is compulsory reading in high schools in Switzerland, but it is also part of the curriculum in several high and elementary schools in France. The writer defended herself by saying that sexual violence was part of the reality of war in Hungary. The argument, however, is flawed, since only the first of the three novels takes place during the time of the global conflagration, while the other two also abound in perversions. On the other hand, they are not simply about violence, but often paraphilias. Moreover, in almost all cases, the perpetrator and the victim live side by side even in peacetime. Despite many controversies, her Trilogy has retained its place among French-language classics and compulsory readings.

Clarity about her works was made significantly difficult by the fact that Ágota consistently portrayed her father in interviews as if he had been sentenced to five years in prison as a military deserter or for political reasons. After all, what else could she have said? Journalist Lívia Ölbei understood that in her life work she “tells everything in the world – what is possible to tell”. Only in “cryptic writing”, as in her diary. Only those who have the key to the solution, her biography without taboos, understand it.

Jenő, Ágota and Attila Kristóf in Kőszeg.

Jenő, Ágota and Attila Kristóf in Kőszeg.For the younger brother, Attila, writing was probably self-therapy in the same way as for Ágota; the creative imprint of a constant, seemingly irrational childhood fear. He is now considered a classic of twentieth-century Hungarian crime writing and a doyen of feuilletonists; his countless detective stories, works of horror fiction, and his two volumes of reports on the work of the Budapest Police Headquarters' murder squad, all helped him to get rid of his demons. Although like his sister, he himself suffered from depression in the middle of his life, their basic worldviews were diametrically opposed. Attila was always driven by the desire for a happy ending, not only in his fictions but also in relation to the knot that arose in his family's life. According to his autobiographic novel, he believed until the end that his parents' names were “written down in heaven”. “Until the last minute I hoped that we would fall on our knees in front of each other, crying for mercy, I thought our souls could be saved”, he wrote. Antónia Turchányi could have been a key player in a healing family conversation, but her strictness and stubbornness were unyielding even after Kálmán's death in 1977.

Attila, unlike Ágota and Jenő, loved his father, although this feeling was mixed with fear towards both parents. Still, he may have been characterized by the ability to “love beyond fate”, the absence of which was pointed out by essayist Zsolt Mórocz in Ágota's works.

In the mid-1980s, already a family man, Attila returned to Kőszeg from Budapest and restlessly searched for the truth of his past, even at the risk of ruin. Just like Sophocles' King Oedipus. However, he found nothing. In almost forty years, the small town apparently forgot the case of the perverted teacher, and the court material was destroyed. Attila could therefore only tell the story, antecedents and consequences of their “expulsion from Paradise” based on his own and his family members' memories. With his twelfth book, “Oedipus circling” published in Hungarian in 1987 – this bitter, honest memoir disguised as fiction – he did as much as possible to save the souls of his family members. (Although he did not name the crime, only vaguely alluded to it.) He gives such a precise and sometimes confidential description of Ágota (under the pseudonym “Zsuzsa”), that it almost seems irresponsible. He could not have guessed that his sister, who had language difficulties, would become a world-famous writer within a few years, whom anyone could easily identify with “Zsuzsa” based on the biographies published about her; and with the help of the works and statements of the two siblings, the family cataclysm can be reconstructed without any particular obstacles. Perhaps there are no coincidences: Ágota wrote her first novel without consultation, in parallel with Attila's Oedipus, and both elaborate on their memories of Kőszeg.

Attila consistently denied the realistic foundations of “Oedipus”, and only after Ágota's death, in the obituary written about her, did he openly acknowledge its autobiographical nature. However, not only the main characters, children and their parents, but also the more important secondary characters are verifiably real figures: for example “Florence” who was murdered in the neighbourhood of the Kristóf family, and Orrnix with her damaged face. Their figures or stories, slightly distorted, were also drawn by Ágota in The Notebook.

Although biographical descriptions of the Kristóf family, memories, interviews conducted in Hungarian, art analyzes, and even the biography and “memorial book” about Ágota published in her graduation town Szombathely in 2016, are all silent about the sexuality prominently displayed in her works and the perverse tendencies of Kálmán Kristóf, the case has always remained a topic of conversation “behind the scenes”. It is not impossible that this was the real reason for the writer's neglect of her homeland.

Since the people directly affected have all passed away: Ágota in 2011, Attila in 2015 and Jenő in 2017, now there should be no obstacle to unfolding the tragedy of the Kristóf siblings factually, processing it on a social level, and commemorating Kálmán Kristóf's at least seventeen victims instead of one-sidedly praising his spiritual legacy.

But by uncovering the terrifying depths and tirelessly fought heights of their true story will Ágota and Attila's wandering souls be calmed? I do not know...

An earlier version of this study appeared in the 2022/3 volume of the journal Vasi Szemle, published in Szombathely.

The book is available in Hungarian. | Contact:

For references see the Hungarian version.